Process Germ Bank

Growing Knowledge From “Seeds”

What is a Process Germ Bank?

A Process Germ Bank is an experimental approach to preserving and sharing knowledge in its most nascent form – as small “germs” or seeds of ideas – so that people in different communities can grow those ideas in their own context.

The project takes inspiration from the 3Ecologies Process Seed Bank and was incubated as part of the Prototyping Social Forms research stream at the Synthesis Center at Arizona State University. More profoundly, it is inspired by agricultural seed banks: just as seed banks store seeds to safeguard plant diversity, a process germ bank stores the “germs” of folk/popular knowledge and ancestral wisdom to protect cultural and intellectual diversity. Instead of preserving only fully formed practices, it preserves the smallest viable units of knowledge—seeds that can be grown, adapted, or hybridized within different communities and contexts.

The goal is to address a key problem in knowledge sharing: how to share knowledge across different communities without extracting it from its original context or homogenizing it. Colonial knowledge transfer is extractive, taking refined ideas or practices out of their local environment and risking loss of their unique “flavor” or value to the original community. The process germ bank is meant to be more regenerative and respectful, enabling “knowledge sovereignty” – giving people the means and opportunity to cultivate knowledge on their own terms and in their own environment.

In short, the process germ bank approach attempts to preserve indigenous and community-based knowledge (like heirloom seeds) and make it accessible in a form that others can plant and adapt, rather than simply shipping out a one-size-fits-all solution.

Key Metaphors and Analogies

Several powerful metaphors underlie the Process Germ Bank concept, making it easier to grasp:

Germs, Seeds, and Seed Banks: The core metaphor is that ideas or practices are treated like seeds (“germs”) that can be stored and replanted. Instead of handing over a fully grown “plant” (a finished product or fully developed idea), one shares a seed that contains the potential to grow that idea elsewhere. This is directly inspired by seed banks used in ecology and agriculture. In the context of knowledge, a process germ bank would hold a variety of idea-seeds, preserving their diversity just as a seed bank preserves many heirloom plant varieties. The assumption is that these idea germs can later be “grown” into full-fledged ideas or processes by others, much like planting a seed and nurturing it to maturity.

Knowledge Ecologies and Terroir: Another key metaphor comes from ecology (and even winemaking): the idea of “terroir”, meaning the particular environment or context in which something grows. Just as a grape’s terroir (soil, climate, terrain) gives wine a unique character, knowledge exists within a specific cultural and environmental context – a knowledge ecology. A “germ” planted in a new place immediately connects the ecology of its origin with that of the new context. If the germ thrives, it shows the two environments have something in common; if it fails to take root, it highlights differences in conditions. The Process Germ Bank uses this metaphor to encourage respect for local conditions: one must consider where an idea-seed is being planted. Terroir in this sense can include climate, terrain, community, culture, or any local conditions that affect whether a knowledge germ will grow. An idea might need certain “soil” (cultural understanding or resources) to flourish, and it may adapt and change when grown in a different terroir. This ecological view reinforces that knowledge is not generic – it’s living and responsive to where it’s cultivated.

Perishability of Ideas: The Process Germ Bank also draws on the metaphor of ideas as living, perishable things, much like fruits or plants. An idea isn’t a static object; it has a life cycle. Ideas “wax, wane, and perish” – they come and go over time. Just as a fresh fruit will rot if not eaten or preserved, a fresh idea can fade away if we don’t preserve it or put it to use. This metaphor emphasizes the importance of timing in innovation: fresh ideas (like freshly harvested fruits) are the most vibrant, but we often try to preserve them for later consumption by drying or freezing. In knowledge terms, “drying” an idea means theorizing it (writing down an explanation), and “freezing” an idea means schematizing it (making a model or diagram). We can even “culture” an idea like yogurt or kimchi, by personalizing it – blending it into our own experience before it disappears. Ultimately, however, new ideas come from fresh play and experimentation, analogous to a plant bearing fresh fruit. The Process Germ Bank encourages generating these fresh idea-germs through playful prototyping, rather than relying only on “preserved” ideas from elsewhere.

These metaphors – seeds and germination, ecological context (terroir), and perishability – provide a vivid framework for thinking about knowledge in a dynamic, life-like way. They shift our mindset from treating knowledge as a static commodity to treating it as living material that must be cultivated, adapted, and continually regenerated.

Types of “Process Germs”

In practice, what exactly is a “germ” of a process or idea?

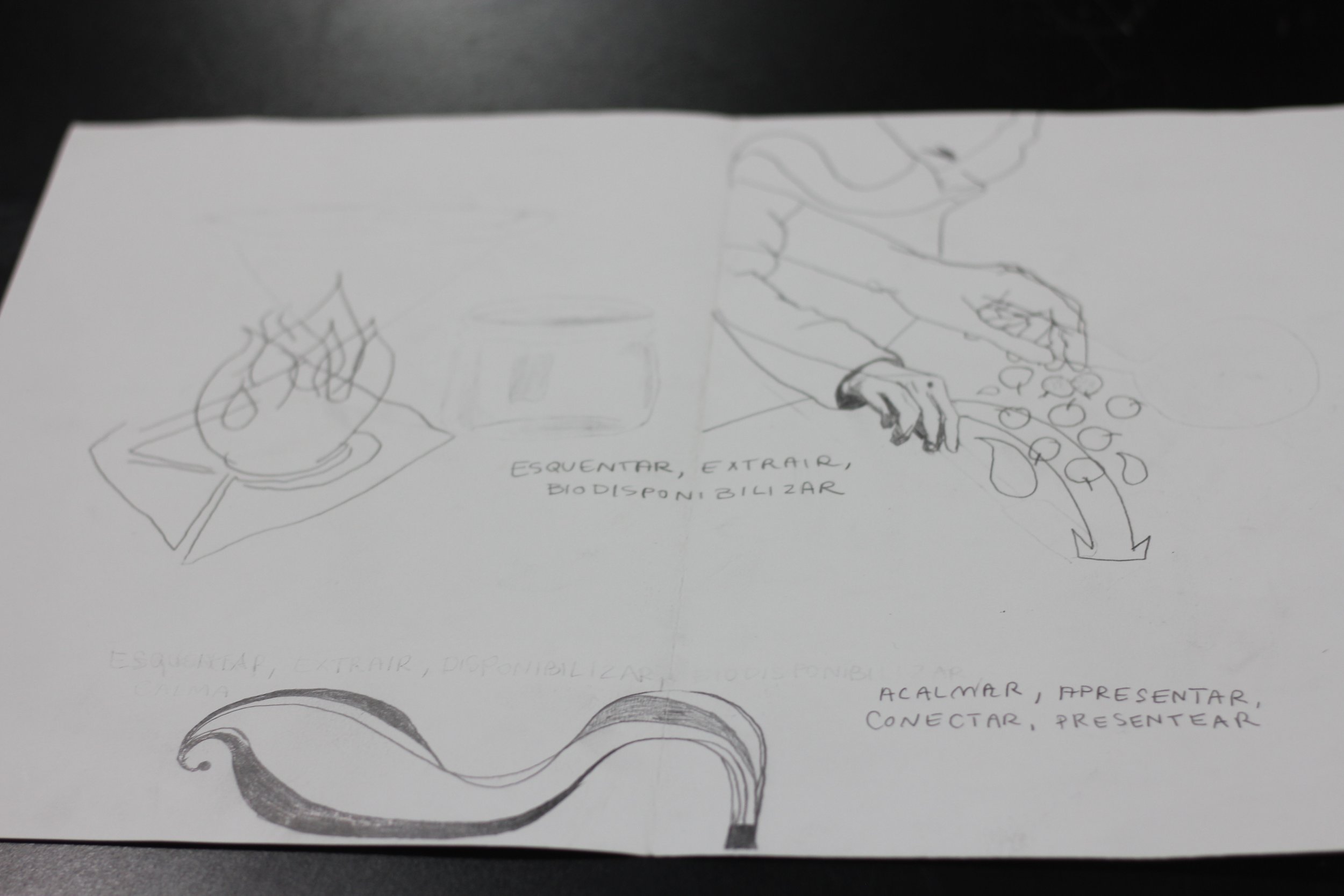

We identify four different kinds of process germs, based on how the germ captures aspects of a process. These categories aren’t mutually exclusive (one germ can be a mix of types), but they help participants recognize different ways a process’s essence can be packaged and shared. The four types are:

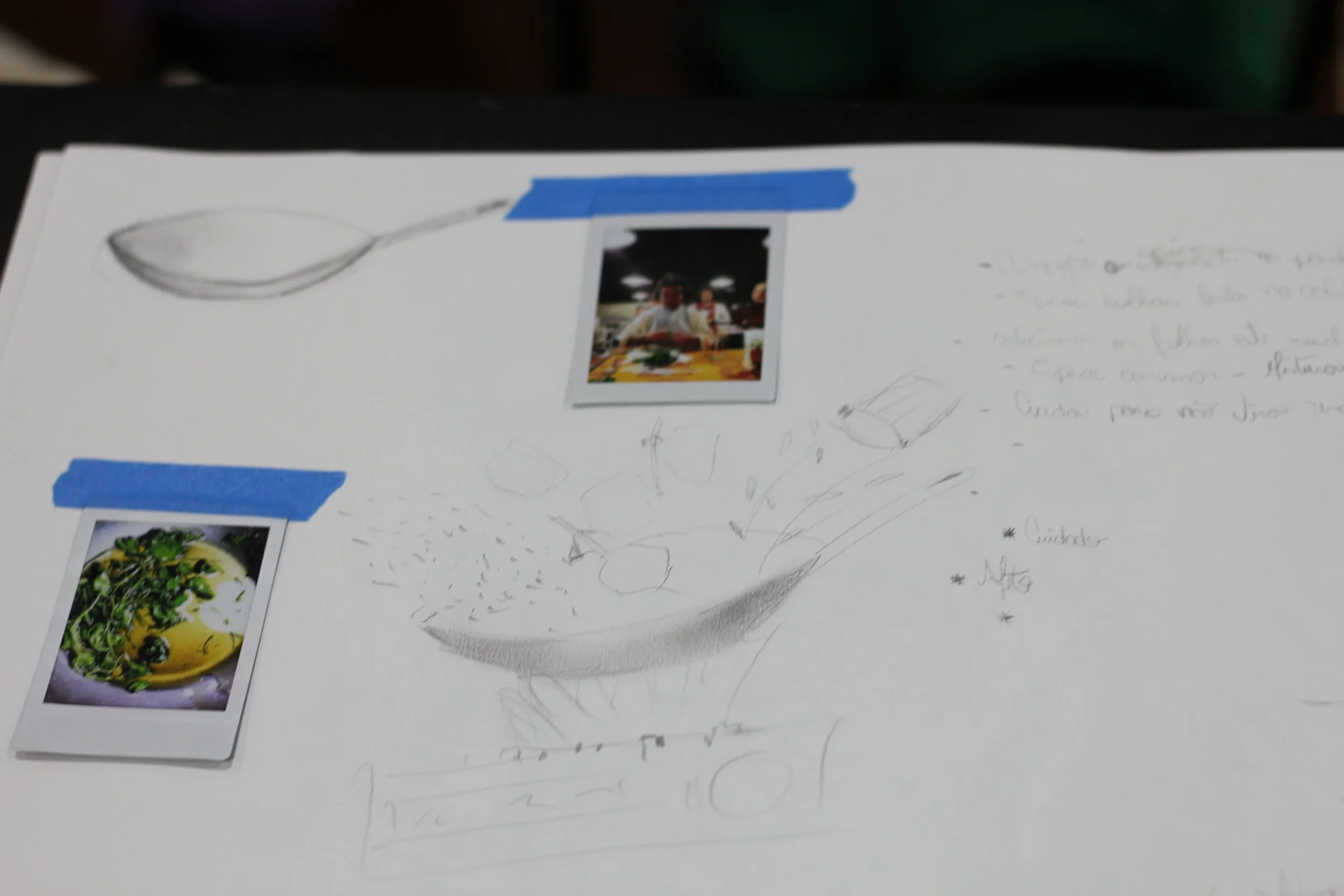

Objective Germs – Residues of a Process: These are the tangible outputs or artifacts left behind when a process is performed. An objective germ is something you can point to or hold – the residue of the activity. Example: In the process of “being a painter,” the paintings created are objective germs of that process. By examining a painter’s finished paintings, someone else might glean how the painting process works or attempt to recreate the style, thus relearning the process from its product.

Subjective Germs – Likenesses of a Process: These germs are representations or images of a process – depictions that capture what it looks or feels like to do. A subjective germ offers a likeness or portrait of the activity. Example: A painting that depicts an artist in the act of painting (such as Velázquez’s famous Las Meninas, which shows the painter at work on canvas) can serve as a subjective germ of the painting process. By seeing an image of the process in action, an observer can infer and emulate aspects of “being a painter” – the posture, tools, environment, etc., effectively recreating the process from its likeness.

Performative Germs – Gestures of a Process: A performative germ is a demonstration or enactment of a process – essentially, acting out the process in some way. It’s like a living seed of the practice, shown through gestures or performance. Example: An actor who, on stage or in film, plays the role of a painter – pacing in front of a canvas, brush and palette in hand, mimicking the behavior of an artist – is producing a performative germ of the painting process. Even though it’s “just acting,” this performance encapsulates key gestures and techniques. Someone watching the performance could learn or relearn the process of “being a painter” by imitating those demonstrated actions.

Constative Germs – Descriptions of a Process: Constative germs are verbal or written accounts that describe a process in words. They capture the idea in a conceptual or explanatory form. Example: An art theorist writing that “every painter recapitulates the history of painting in their own way” is providing a constative germ of the painting process. This statement distills an insight about how painters work, and from such a description one could derive guidance or principles to recreate the process (for instance, a painter might take it as advice to study past masters and then develop their own style).

Each type of germ provides a different avenue for sharing knowledge. In a process germ bank, you might find any combination of these: physical artifacts, images or recordings, live demonstrations or how-to enactments, and written or spoken explanations. All are seeds that contain something essential about the process, which others can then take and cultivate. By recognizing these types, workshop participants learn that they can package their knowledge in multiple forms – not just by writing a manual (constative), but perhaps also by sharing a key tool or product (objective), an illustrative story or image (subjective), or a hands-on demo (performative). Often, mixing these forms makes the germ stronger, as each type can complement the others in conveying the process’s essence.

Transporting, Transplanting, and Growing Knowledge

An important distinction in the Process Germ Bank framework is how knowledge is transferred or shared between different places or communities. We outline three modes of knowledge mobility, using the plant analogy to differentiate them :

Transporting Knowledge: This is like shipping a finished product from one place to another. In knowledge terms, it means taking a fully developed idea or “knowledge product” and moving it elsewhere. For example, a completed curriculum, a set of instructions, or a technology is packaged and delivered to a new community. While this can spread knowledge quickly, it often doesn’t account for local context – it’s as if you exported fruit from one climate to another. The knowledge arrives as a done thing, but it might not take hold or regenerate locally.

Transplanting Knowledge: This approach is like digging up a mature plant (with roots and all) and replanting it in new soil. In practice, transplanting means taking an established practice or expertise from one community and implanting it in another. For instance, bringing in experts or a whole program and trying to establish it in a new setting. This acknowledges the need for roots (it’s not just a fruit, it includes the living plant), but those roots are from another soil. The risk is the “plant” may struggle if the new soil conditions aren’t right. It might survive, but it could also wither if it cannot adapt, and the process can disrupt local practices (much like an invasive species or a delicate plant that doesn’t suit the climate).

Growing Knowledge from Germ to Fruit: This is the method championed by the Process Germ Bank. It involves sharing only the germ of the knowledge – a seed – and cultivating it anew in the local context. Instead of handing over a complete solution, you provide the starting point (the idea kernel, the process germ) and the new community grows it in their own “soil” with their own methods. This is analogous to planting a seed from elsewhere and nurturing it on local land. The outcome might not be identical to where it came from (just as a plant might adapt to local conditions), but it allows the knowledge to truly take root in the new context. This approach encourages learning and adaptation, and it respects the integrity of both the original knowledge and the new environment. Because the knowledge is grown locally, it tends to be more sustainable and empowering – the community becomes the knowledge owner and cultivator, not just a consumer.

The Process Germ Bank focuses on the “growing from germ to fruit” approach, believing it to be more regenerative and equitable. Transporting and transplanting knowledge, as noted, often end up being extractive – they can strip knowledge from its source or impose it on a new setting without integration. By contrast, growing knowledge from shared germs is collaborative and generative. It gives participants the chance to innovate and customize, and acknowledges that different places and peoples may grow the “same” idea differently. In fact, observing how a germ grows in two different places can be very instructive: if it grows successfully in both, those places share some common ground; if it only grows in one and not the other, it reveals a difference in cultural or practical ecology between them. In that way, the germ exchange not only spreads knowledge, but also maps relationships between communities (just as certain seeds only thrive in particular climates, certain ideas might only thrive in particular cultural conditions). Overall, this distinction highlights why the Process Germ Bank is not just about moving knowledge around, but about nurturing knowledge ecosystems and maintaining the unique “flavors” (terroir) of ideas even as they travel.

WORKSHOPS

How can these ideas be put into practice in a workshop setting?

The Process Germ Bank concept has been developed into a workshop format where participants (often keepers of traditional, folk, or specialized knowledge) actively identify, cultivate, and share their own process germs with each other. The workshop is designed to balance theoretical insight with hands-on practice, so that participants come away with both a deeper understanding of knowledge processes and practical tools for exchanging their know-how. The overall approach is highly participatory and creative – it “revolves around the practice of prototyping” rather than lecture, meaning participants will be making and trying things out (playing with idea germs) rather than just discussing outcomes. The tone is intentionally playful and exploratory, reflecting the idea that fresh ideas are born from play. Below is a structured way a workshop might proceed:

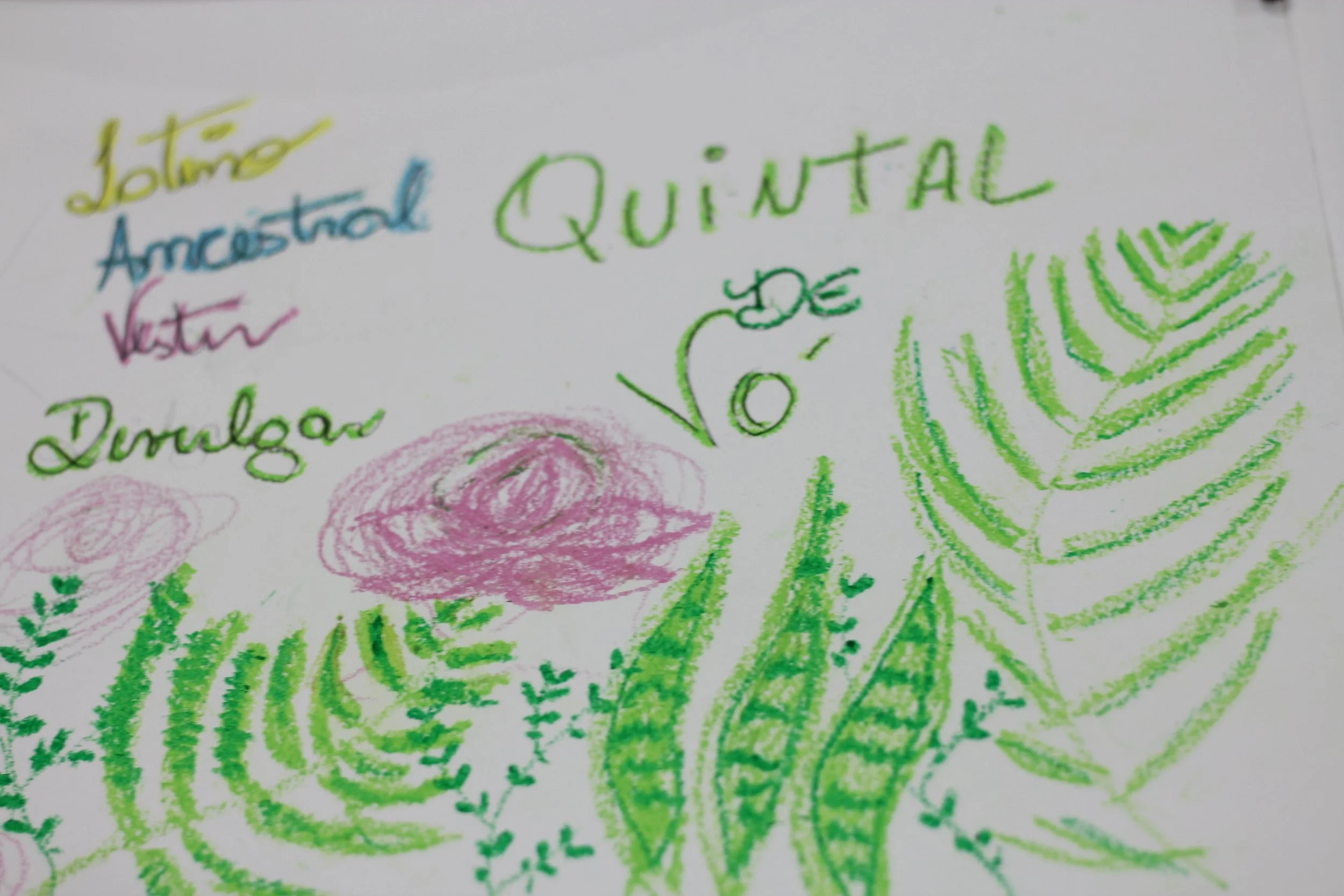

Identifying the Germ – Capturing the Seed of a Process: To begin, each participant is encouraged to think of a particular knowledge or process they hold that they would like to share – something from their craft, tradition, or expertise that could be valuable to others. The key is to articulate the “germ” of that process, i.e. the essential kernel that could grow into the whole practice. Facilitators might guide this with reflection questions. For example: What are the different varieties or strains of your process? If your process were a plant, what different breeds or variations does it have? Also, in what environments or terroirs can it take root, and how do different conditions change the way it grows? These prompts help participants pinpoint what is core to their process and what elements are flexible. By considering the “terroir” of their idea (the cultural or environmental conditions it needs), participants identify which aspects of their knowledge are sharable seeds and which are tied to local context. At this stage, they also decide on a form for their germ: Will it be a story they tell (constative)? A demonstration or gesture (performative)? An artifact or example they’ll show (objective)? Or perhaps a mix of these? The emphasis is on keeping it simple and potent – like a seed that carries the DNA of the whole. Each participant essentially comes up with a prototype or model of their process in miniature, which can later develop in many directions.

Cultivating and Prototyping – Nurturing the Germ: Once the idea-seed is identified, the workshop moves into developing it and preparing it for sharing. This is akin to planting the germ in a controlled setting and tending it so it’s strong enough to be passed on. Participants might work individually or in small groups to flesh out their germ and imagine how it grows. Facilitators can introduce the full suite of planting metaphors to guide this cultivation stage: for instance, How will you nourish your process germ as it develops? Does it need specific resources or support (water, nutrients)? Does your process require a trellis – some structure to hold onto as it grows (perhaps a framework or set of principles)? How can you tend to your process to increase its fruitfulness – what practice or care does it need over time? Are there any pests or weeds that might threaten it – common pitfalls or challenges that could “blight” your idea? By thinking through these questions, participants effectively prototype how their knowledge can be developed from germ to full form. They might create quick sketches, diagrams, or storyboards (schematizing the idea), or do a trial run of demonstrating their process (a rehearsal). For example, someone sharing a traditional dance might identify the “seed” (a basic step or rhythm), then consider what music, space, or mood nourishes it, and what might hinder it. They could then do a short practice demonstration for the group as a prototype. Throughout this stage, the focus is on process over outcome – it’s iterative and exploratory. This approach aligns with the philosophy that play and experimentation (“rehearsal”) precede the final performance. Participants are essentially rehearsing with their idea germ, getting feedback, and refining how to communicate it. This not only strengthens the germ for others to use but often gives the originator new insights into their own practice.

Sharing and Growing Together – Exchange of Germs: The culmination of the workshop is a collective sharing, where each participant adds their polished process germ to the “bank” for others to access. Practically, this could be a session where everyone presents their germ in its chosen form – tells their story, shows their artifact, performs their demonstration, or hands out their mini-instruction – thus depositing it into the communal repository. The idea is that each germ is now available for others to borrow and plant. Participants are encouraged to exchange germs and try cultivating each other’s ideas, much like swapping seeds in a community seed bank. For example, person A might take person B’s germ and see how that process might work in A’s own community or context. This step is where the real cross-pollination happens. It can be eye-opening: sometimes a germ from one context will take root easily in another, revealing a compatibility or similarity between the two cultures; other times a germ might struggle or require adaptation, highlighting important differences. Both outcomes are valuable. In the workshop, if time allows, participants could even do a small experiment – such as pairing up and attempting to apply each other’s germ on the spot in a new scenario – then share what happened. At minimum, the group discusses how they might use the germs they received and what modifications might be needed. The facilitators ensure that by the end, each participant has not only contributed a germ but also taken away one or more germs from others, along with an understanding of how to cultivate them. The Process Germ Bank thus lives up to its name: it becomes a repository of diverse, living knowledge seeds that the group collectively maintains. Everyone leaves with a “kit” of idea-seeds and the skills to grow them. Importantly, this sharing phase underscores a respectful exchange – it’s reciprocal rather than extractive. Each knowledge keeper’s contribution is acknowledged (preserving credit and cultural context, akin to labeling seeds with their origin), and each receiver is responsible for growing the idea in a way that honors its source. The workshop might even discuss guidelines for using someone else’s germ – for instance, how not to appropriate or commodify it, but to let it enrich your own practice in a collaborative spirit.

Throughout these steps, the workshop facilitator connects the activities back to the theoretical insights to deepen understanding. For example, after the sharing, the group might reflect: What did we notice about how ideas change when transplanted? What does it tell us about our different “knowledge ecologies”? This can lead to a conversation about maintaining diversity vs. forcing uniformity, echoing the seed bank philosophy of protecting many varieties. The notion of preserving vs. fresh growth might also come up: participants can recognize which parts of the workshop involved preserving knowledge (writing it down, making models) and which parts involved fresh play (improvising and testing new variations), reinforcing that both are important. By the end, participants have learned how to identify the core of their knowledge, how to nurture it, and how to pass it on in a healthy way. They have essentially practiced being both farmers and chefs of knowledge: farmers in growing and tending idea-seeds, and chefs in creating something usable from raw ingredients (including culturing or preserving ideas as needed).

Banco de cohencimentos germinates 2024

Com Muindi Fanuel Muindi e Romária Sampaio

@SESC POMPEIA, São Paulo, Brasil

July 10 - July 12, 2024

ANTICIPATION 2022 @ ASU

18 November 2022

Muindi Fanuel Muindi, Sha Xin Wei, Dulmini Perera, Vangelis Lympouridis, Desiree Foerster, Mark Balzar, with Nadia Chaney, John MacCallum, Teoma Naccarato, Satinder Gill

“Detourning” the notion of anticipation, the interdisciplinary and international collective Prototyping Social Forms (PSF) offers a series of workshops and a curated panel on enacting alternatives to what is presently the case so as to better imagine, sketch, inhabit and reflect on other ways of living in the world that may be obscured by present narratives.

Inspired by “seed banks” developed and maintained by horticulturalists and ecologists, the PSF Process Germ Bank is an experimental infrastructure for sharing germs of research- creation practices and for developing signature methods for probing and promoting diversity within different knowledge ecologies. Hybridizing metaphors, we offer a “seed ball” of process germs to try out in the terrain of the Anticipation Conference 2022.

The “PSF: Un Altro Mondo È Possibile” stream consists 90-minute techniques workshops followed by one 90-minute curated session for reflections upon the techniques workshops and related work. Each techniques workshop will involve the “sprouting” and tending of two process germs.

10:00-11:30 | Techniques Workshop #1: “Enacting and Sensing Process”

12:30-14:00 | Techniques Workshop #2: “Enacting and Sensing Body”

14:30-16:00 | Curated Panel: “Un Altro Mondo È Possibile”

Walton Center for Planetary Health, Room 409